A book can feel like the safest place in the world—until it doesn’t.

IF you are one of my lovely dark romance readers whose mouth starts to water the longer the trigger warning list goes on: This post is probably too boring for you. You might want to be good for me and move on to the next, where we discuss why some people seem to crave the most violent, morally gray men/women, because they feel calm and peaceful after (no judgement!). If you feel outraged by this paragraph and want to rant about them being porn addicts or possessed or un-normal or anything, please leave altogether. Discrimination and bullying is not welcome on my pages.

Most of us pick up a story expecting a certain kind of experience: distraction after a long day, comfort when we’re lonely, a little thrill before bed, a reason to feel something on purpose. And usually, that’s what we get. Especially if you are an „advanced reader“, you know your favorite tropes, storylines and authors. And still, sometimes a scene lands differently than we expected. Your chest tightens. Your stomach drops. Your jaw tightens. You find yourself skipping lines, reading faster, or not reading at all. An image forms in your mind. A memory might tap you on the shoulder. You close the book and realize you’re not “just entertained”—you’re activated, maybe even aggrivated. And not in a good way.

That gap between what we thought we were signing up for and what our nervous system actually experiences is where trigger warnings (and content notes) come in.

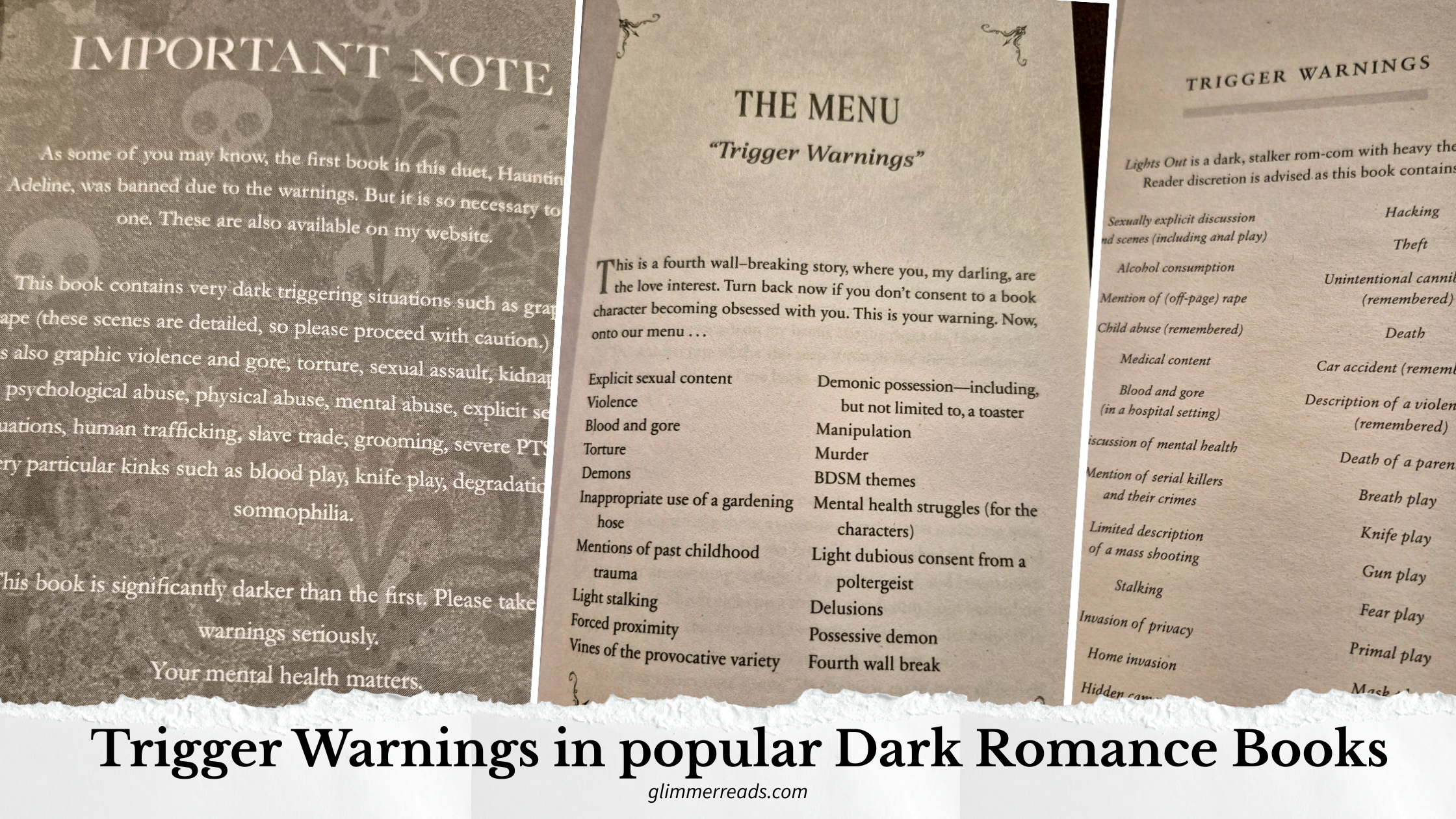

Books have gotten banned for their list of trigger warnings alone (a prominent example: H.D. Carltons „Haunting Adeline“). Trigger Warnings serve a very specific purpose:

To help readers choose—more intentionally—the emotional journey they’re about to take.

Unfortunately, a culture has developed where it seems „cool“ or „fly“ or „lit“ (depending on your birth year) to hunt after the most devastating content a reader can find.

It almost feels like a „desensitization“ to the gruesome experiences some characters are facing – all by the will of their masters, the authors. Let me just point out: Most of the stories out there in fiction books are made up – thankfully. Because the amount of trauma some characters have to endure to reach whatever goal they are chasing / given is shocking. BUT being a therapist I also know that many people have lived through traumatic experiences and have a valid need for safety.

Reading Is an Emotional Experience (Not Just Entertainment)

We tend to talk about reading like it’s mostly cognitive: plot, prose, pacing, character arcs, twists. And yes, that’s all in there. But reading is also deeply personal.

Your brain doesn’t process a story the same way it processes a grocery list. When you read vivid scenes, your body responds: heart rate shifts, muscles tense, breath changes. Imagery isn’t just “described”—it’s simulated. Identification isn’t just “relatable”—it can feel personal. A character’s fear can echo in your own system, even if your life looks nothing like theirs. Which is why many readers (especially in graphic romance novels) talk about their Book Boyfriends and their newfound curiosity in questionable sexual activities (yes, I am talking about the mirror scene, the in-the-cave-boat-scene, the reverse-harem-multipenetration-scenes and many others, you are welcome!)

This is why books can be so comforting (and exciting). It’s also why they can be anything from confusing to destabilizing or downright (re)traumatizing. And yes, I would love to include audio-books, which productions have become so professional that one get’s goosebumps from the males deep voices alone.

A “safe” story isn’t safe because nothing bad happens in it. It feels safe because the level and type of emotion it evokes is something your system can hold today. And that “today” part matters. The same reader can have totally different responses to the same content at different times in their life.

It’s also normal to have mixed reactions. You can love a genre and still feel impacted by specific material within it. You can be a horror reader who doesn’t want child harm. You can devour thrillers but skip graphic sexual assault. You can adore romance but feel your throat close up when a storyline hits too close to home. None of that makes you inconsistent. It makes you human. And it is completely fine to dnf a book if it gives you the icks.

This is the perspective I wished more readers had: you are not choosing a book only for its premise. You’re choosing an emotional experience.

And increasingly, readers are naming that openly. On BookTok, Bookstagram, Goodreads, Reddit—people share not just recommendations, but reactions. Content notes have become a form of community care: “I loved this, but here’s what’s in it.” It’s not about declaring a book dangerous. It’s about acknowledging that stories make contact with real nervous systems in real bodies. The community takes good care of each other… or don’t they?

Trigger warnings exist in that same spirit: not to police what gets written, but to help readers choose what they’re ready to feel.

What Trigger Warnings Are — and What They’re For

In plain language, a trigger warning is a brief, content-specific heads-up that a book includes potentially distressing material. It tells you what kind of content might be present so you can make an informed choice about whether—and how—you want to engage with it.

That’s the heart of it: informed choice. As you can read in the header above, authors want to keep their readers safe and happily-reading, not shaken to the core

A good trigger warning supports three things.

First, autonomy. You get to decide what you take in. Not based on what you “should” be able to handle, or what everyone else says is “not that bad,” but based on your own history, bandwidth, and preferences. You are free to choose any book you want – just as you are free to decide what book(s) not to read.

Second, preparation. Sometimes you still want to read the book—you just don’t want to be blindsided. Knowing what’s coming can let you choose a better time, a better setting, or a more supportive way to read.

Third, pacing. Trigger warnings aren’t only about avoiding content. Many readers use them to manage intensity: to slow down, to buffer, to take breaks, to read with the lights on, to avoid starting something heavy right before sleep.

It’s also worth clarifying the word “trigger,” because it gets used in two different ways.

Clinically, a trigger refers to something that activates a trauma response—often a sudden, body-based reaction that can feel like you’re back in a past experience. People with PTSD (and other trauma-related responses) might experience intrusive memories, panic, dissociation, or intense physiological arousal when exposed to reminders of what happened.

In pop-media-youth-language, people also use “triggered” to mean “upset,” “uncomfortable,” or “sensitive.” That usage can be imprecise, but it points to something real: content can still hit hard even if it doesn’t produce a full trauma flashback. And readers deserve language for that too.

In publishing and reader spaces, you’ll see “trigger warnings” and “content notes” used interchangeably. Sometimes “content note” is preferred because it sounds more neutral and less clinical. Either way, the function is similar: a heads-up that helps you choose your experience.

If you strip away the internet noise, trigger warnings are not a referendum on toughness. They’re a tool for agency and in many cases self-care or self-protection

What Trigger Warnings Are Not

Trigger warnings get misunderstood partly because we load them with meanings they weren’t built to carry. So let’s clear a few things up.

They are not censorship.

A warning doesn’t remove content from a book. It doesn’t demand the author change their story. It doesn’t ban a theme. It adds context so the reader can consent to the experience. If anything, it’s an argument for readers having more information, not less.

They are not a moral judgment on the author or the genre.

A book can include abuse, violence, self-harm, addiction, or sexual assault and still be meaningful, cathartic, or artistically important. Dark stories can tell the truth about human experience. They can give language to things people couldn’t name. They can help readers feel less alone. Trigger warnings don’t declare a book “bad.” They simply say: this contains X.

They are not automatically spoilers.

This is the one people worry about most, and I get it. Part of reading is not knowing. But there’s a big difference between “this book includes suicidal ideation” and “the main character attempts suicide in chapter 27 after being betrayed by X.” One is a category of content; the other is plot detail.

Responsible warnings can be offered at different levels of specificity. Some readers prefer vague warnings that protect surprise. Others need more detail to feel safe enough to engage. That’s why you’ll sometimes see a general note up front and a more detailed list available behind a spoiler toggle, on a website, or at the back of the book.

They are not a guarantee of safety.

No content note can predict every reader’s reaction. Two people can read the same scene and have completely different experiences. Something that’s not on any standard warning list—like a specific smell described in a scene, or a certain family dynamic—might be the thing that hits you hardest. A warning is a tool, not a shield.

And finally: tropes are not the same as trigger warnings.

A trope signals a pattern (enemies-to-lovers, forced proximity, second chance). It does not tell you the intensity, the explicitness, or the emotional texture of what happens on the page. “Dark romance,” for example, can mean a wide spectrum—from morally gray and intense to explicitly violent or coercive. The label points you toward a vibe, not a dosage.

There is a ton of really funny reels out there, where „experienced readers“ point out the different levels of „smut“ or „fantasy romance“ in a book. It is hilarious, look it up!

Warnings help with dosage. Tropes help with flavor. You might love the flavor and still need to know the dosage.

A Therapist’s Perspective: Curiosity Doesn’t Always Mean Readiness

Here’s something that shows up all the time in therapy—and in reading life too:

Curiosity doesn’t automatically mean readiness.

You can be intrigued by a book. Or you have read ALL books by a certain author. You can love the premise. You can even enjoy intense or dark stories in general. And still, on a particular week, your nervous system might not be resourced for that experience. Listen to your body!!!

This isn’t weakness. It’s context.

Readiness shifts depending on what else your system is carrying: grief, burnout, illness, anxiety, hormonal changes, sleep deprivation, recent stress. Something that felt manageable before might feel overwhelming now. And that’s not a failure of resilience—it’s information.

In therapy, we talk about pacing: how to approach difficult material in a way that doesn’t flood the system. The same principle applies to books, even when the material is fictional. You’re still having a real experience while you read. From a mental-health perspective, choosing timing and pacing isn’t restriction—it’s skill. Sometimes, it helps to have a book bestie at hand to talk/text with. The low key funny and the deep end troubeling. Others prefer to write down their thoughts about certain aspects or chapters in a book. Just make sure you find the right outlet for yourself to enjoy a book, not feeling weighed down by it, ok?

There’s a popular mis-belief that pushing through discomfort only makes you stronger, and avoiding it makes you fragile. But nervous systems don’t work that way.

Forced exposure often backfires. When the body feels trapped, it doesn’t learn resilience—it learns danger.

Resilience grows through choice, support, and self-trust.

Understanding what trigger warnings are is only the first step. The harder—and more personal—question is how to decide what you are actually ready to read at any given moment.

→ Curiosity Isn’t Readiness: How to Choose Books Your Nervous System Can Hold

No responses yet